458th Bombardment Group (H)

458th Bombardment Group (H) Synopsis

Group tail markings Feb – May 1944 (left) and May 1944 – 45 (right). Postwar memorial (center) on the airfield, currently Norwich International Airport.

(Rudders, courtesy Kelsey McMillan; Memorial photo: Rob Maguire)

The creation of a new, heavy bombardment group composed of four existing bombardment squadrons, the 752nd, 753rd, 754th and 755th began in March 1943. The number 458 was specified on or about April 24, and this unit was activated July 1, 1943 at Wendover, Utah. Personnel and hardware assembly started at Gowen Field, Boise, Idaho July 28. Training was accomplished at airfields in Boise, Orlando and Pine Castle, Florida, Kearns, Salt Lake City and Wendover, Utah and Tonopah, Nevada.

Project 92336 reassigned the 458th to the European Theater of Operations (ETO). Its ground echelon left Tonopah by rail January 1, 1944 en route to New York’s Port of Embarkation and the USS Florence Nightingale for their overseas journey. They arrived at Greenock, Scotland January 31 and their base, Army Air Forces Station 123, Horsham St. Faith, Norfolk County, England February 1. This airdrome had been a permanent Royal Air Force facility and soon the new arrivals were attracting envy from some of their peers stationed in lesser quality quarters throughout East Anglia.

Tonopah Army Air Field 1943 (left), and RAF Horsham St Faith (right) in 1944

Aircrews departed Tonopah for Hamilton Field, California to pick up new and additional B-24s. Singly and in small groups of 3-4 aircraft, the crews flew their “Liberators” to England via Brazil and West Africa, joining the support elements on the home base by February 18. Additional personnel training and aircraft modifications began immediately as this fledgling group prepared for its coming aerial battles.

The 458th’s first combat assignment came February 24, 1944 in flying a diversionary mission along the Dutch coast to draw enemy fighters away from Germany while experienced units struck deep into the enemy’s homeland. A similar mission was flown the next day along the French coast. Initial bombing sorties began March 2 with a strike on Frankfurt, Germany. All ships returned to base. Then on March 6 the 458th flew in the first mission the 8th Air Force completed on Berlin. Five crews did not return from this one – the highest total loss of any mission for the remainder of its combat tour.

On June 6, D-Day was a hectic one for the Group in flying three missions with 59 aircraft being dispatched. As weather conditions improved during summer, operations increased and the 458th completed 100 missions before June expired.

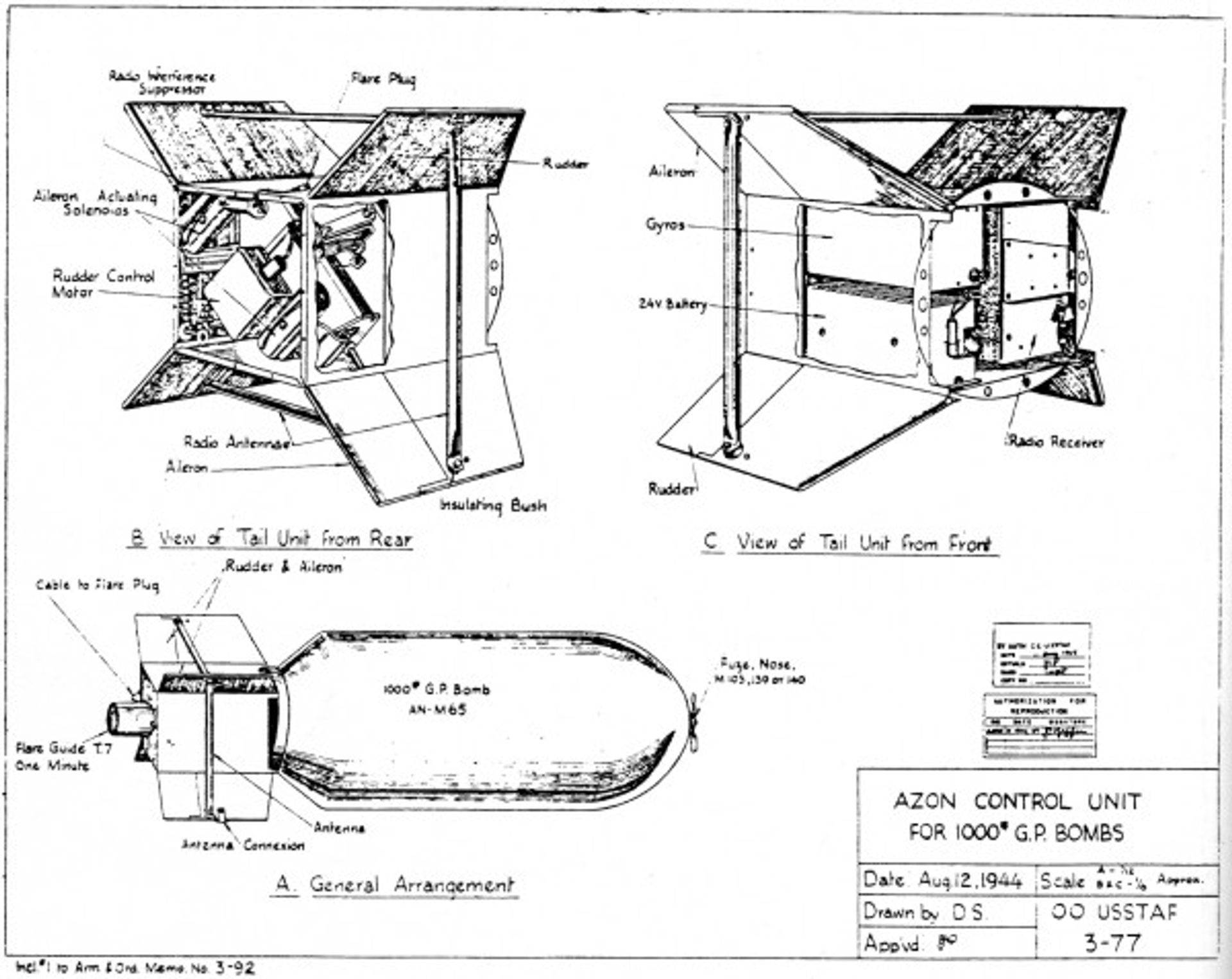

During the month of May a cadre of personnel brought a specialized and highly classified project to Horsham to test a new, revolutionary weapon for the 8th Air Force. Ten crews, initially, were to deliver a cargo of “controllable” bombs on bridges and other selected targets in preparation for the D-Day invasion of fortress Europe. Those bombs were named AZ(imuth) ON(ly) and amounted to a projectile whose course could be altered after it was released from the aircraft.

The Azon Bomb consisted of a unit with a radio receiver bolted to a standard 1,000-pound bomb which replaced ordinary fins. After release from the bomb bay, bombardiers used a transmitter in the aircraft to correct azimuth errors while the projectile fell by activating movable fins on the control unit. Range errors could not be changed, however. This weapon also employed a flare of different colors, and the controller had to observe the bomb’s flight path down to the objective. Weather conditions over the Continent were not at all favorable for this type of activity during the test period. But one practice runs and 13 actual Azon missions were made before the project was discontinued in September. Under ideal conditions, Azon Bombs proved to be a very effective weapon for use in pinpoint bombing requirements more than saturation-type bombing. But more importantly, the testing pointed the way for use in other “smart” bomb projects in future years.

When September arrived, Allied ground forces were making rapid advances across Europe as they pushed the enemy back toward his homeland. Progress was so good, in fact, America’s Third Army was outrunning its own supply sources, and gasoline for its armored vehicles became in critically short supply. All of the 2nd Air Division heavy bomber groups, including the 458th, suspended bombing operations, stripped their aircraft down to bare essentials and began hauling fighter auxiliary tanks filled with gasoline instead of bombs.

The 458th flew 13 of those “truckin” missions to Lille, Clastres and St. Dizier, France in delivering 727, 160 gallons of fuel to the doughboys. Aircraft were manned with skeleton crews, and they flew at minimum altitudes to avoid detection by enemy radar. The airmen received no mission credit for these flights, and all expressed more apprehension over carrying the volatile gasoline than a full load of bombs. A total of 494 aircraft were dispatched for truckin’ operations, of which six were lost in accidents, and one lost to enemy action. Four others were damaged and had to be salvaged.

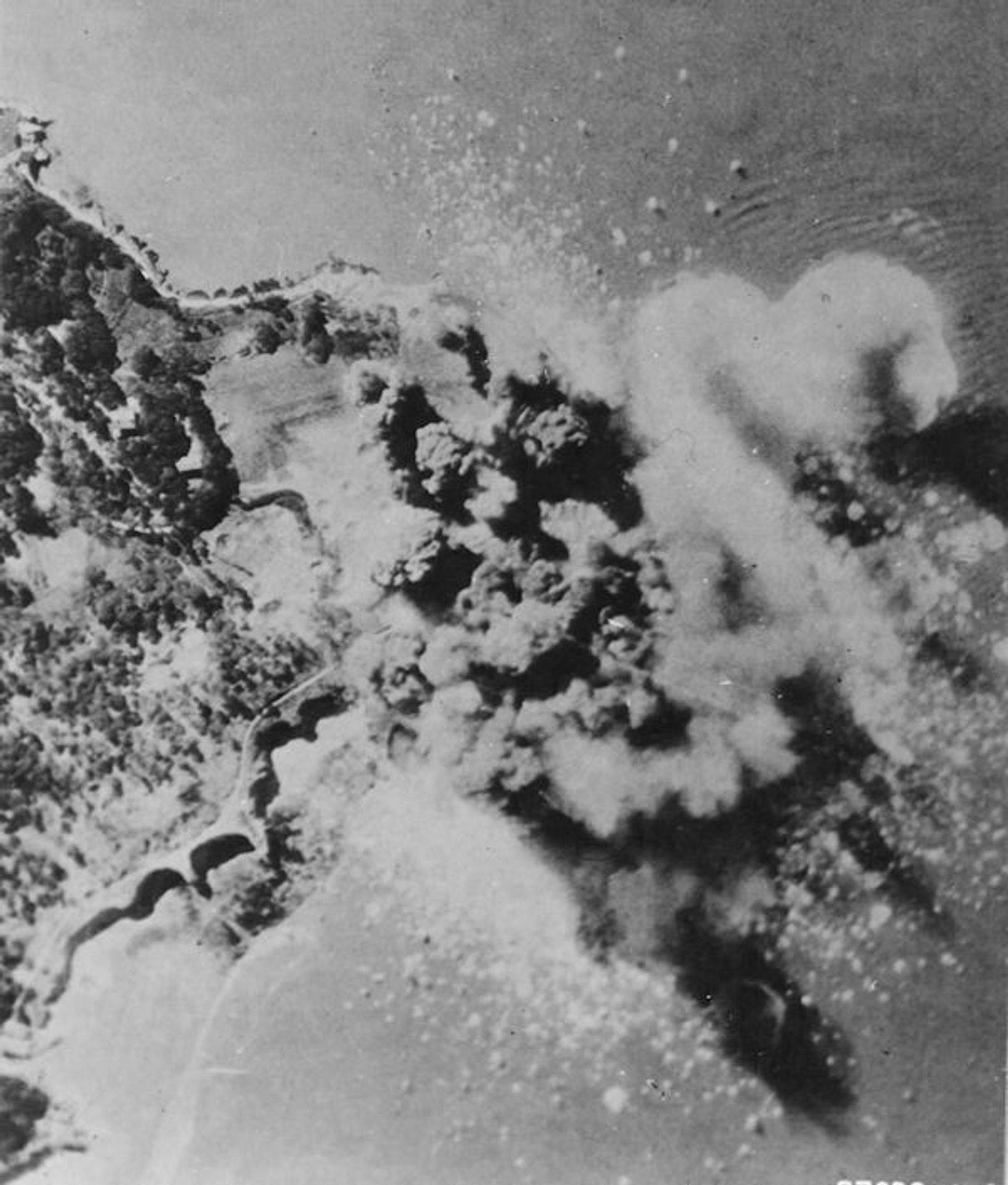

On April 15, 1945, the 458th participated in an unusual sortie to Royan, France (left). More than 120,000 enemy troops were still occupying an area along the Gironde Estuary that French forces had been unable to clear out. Further ground action appeared to be very costly and lengthy. Aircrews loaded containers of “jellied gasoline” into their bomb bays and flew the mission. This was the first use of Napalm in the ETO, and it was successful. The Group’s last mission occurred on April 25 with a strike on a railroad target at Bad Reichenhall, Germany and it proved to be one of the few “milk runs” this Group had.

The mellow rumble of Liberator engines was very prominent over the East Anglia countryside on June 14 as aircrews began taking off for the USA and possible Pacific war zones. Air traffic controllers in the Horsham control tower would no longer respond to radio calls for “Hulking”. Once again, the ground echelon went by sea for their return voyage home when the boarded the Queen Mary on July 6 for New York. Following R&R leave, the unit reported to Walker Field, Kansas then to March Field, California for B-29 transition. But Japan surrendered before advance training could begin and the Group was deactivated officially October 17, 1945.

The 458th tally sheet for its 14-month overseas tour, includes 230 combat, 14 Azon bomb, 15 Truckin’ and two diversionary missions. It delivered 13,168 tons of bombs and recorded 28 enemy fighter “kills” plus several more probables. Just prior to D-Day, the Group led the entire 8th Air Force in bombing accuracy.

This Group won no awards from the Army Air Forces nor the 8th Air Force although it had a prominent role in every major air campaign in the ETO after arriving for duty. It was cited four times by the 2nd Air Division for outstanding accomplishments. First, for completing 100 missions by June 1944. Secondly, for destroying a bridge at Blois-St. Dennis, France on June 11 that was vital to the enemy. Thirdly, for completing 200 missions by March 1945, and fourthly, in the period of September, 1944 – February 1945 for “a very low level of venereal diseases – lower than other stations and the 8th Air Force as a whole.”

In September 1944, General Order 3982 awarded the 458th a Distinguished Unit Citation. However, on November 9, 1944 the Group was dispatched to Metz, France on a mission in atmospheric conditions whereby any conceivable aerial mishap might occur. One did! Some bombs from 458th aircraft landed on American forces engaged in ground fighting and prestigious powers demanded retribution. It came swiftly, in December, by a revocation of the DUC Order, but it remained for almost a sadistic length of time and manner. There is no evidence of the Order nor its revocation in official Group records now.

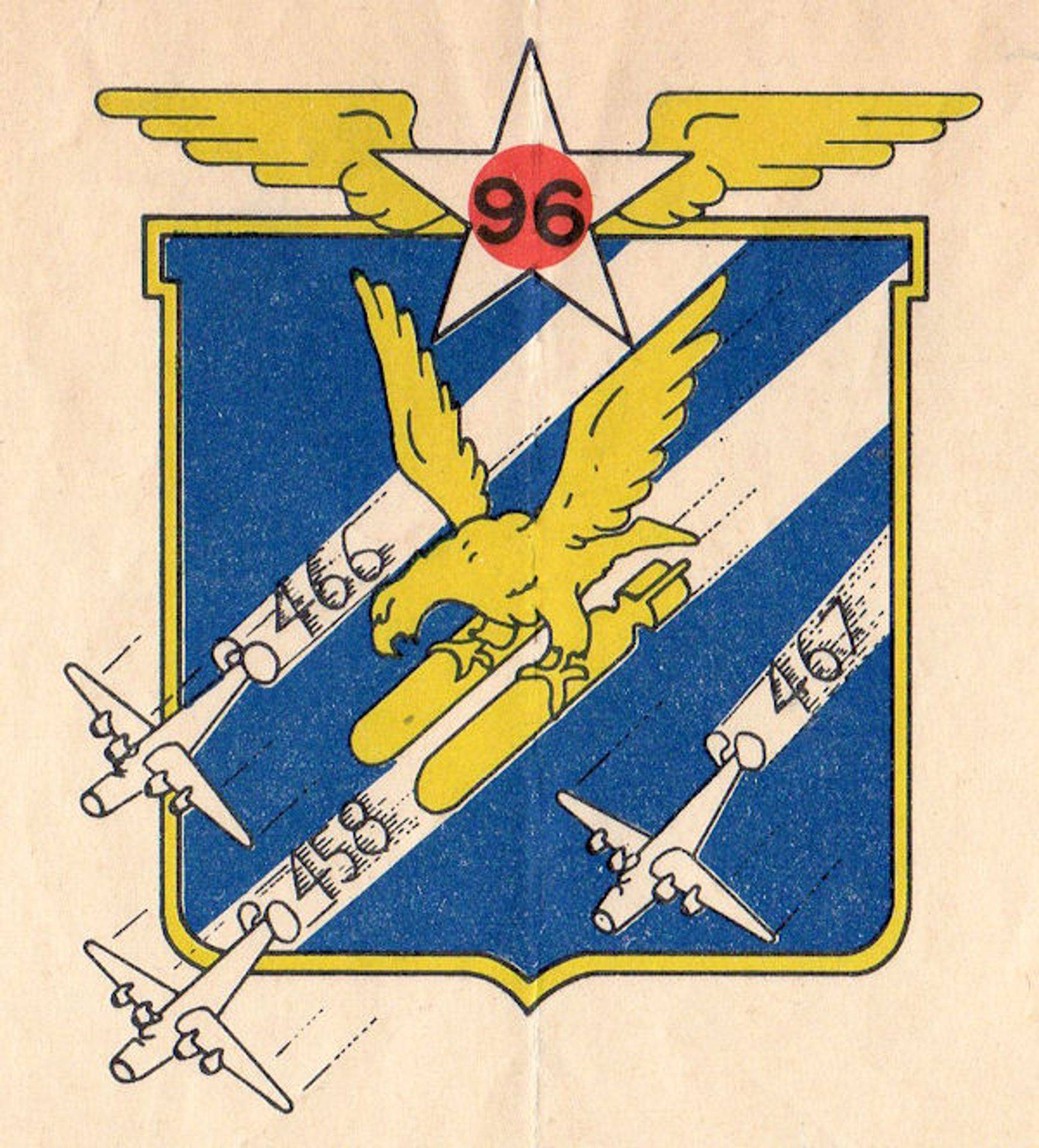

The 96th Combat Bombardment Wing was composed of the 458th, 466th and 467th Bombardment Groups, and their aircraft markings [beginning in May 1944] were: fire engine red ovals [outside rudders] with a white stripe bearing a red squadron call letter. The 458th had a vertical stripe, the 466th horizontal and the 467th diagonal from front to back. A figure/letter grouping just aft of the waist window designated individual squadrons. The 458th Squadrons were: 752nd – 7V, 753rd – J4, 754th – Z5, and 755th – J3.

Initial markings for all 2nd Air Division aircraft were similar, but also featured a large group letter blue on a white disc applied to the ovals. A change in markings occurred after the olive drab paint scheme on aircraft gave way to the natural metal finish in about April 1944. The 458th’s letter was K and it also appears on the upper surface of the right wing.

Major campaigns the 458th participated in were: Air Offensive, Europe, March 2 – June 5, 1944; Normandy, June 6 – July 24, 1944; Northern France, July 25 – September 14, 1944; Rhineland, September 15 – March 21, 1945; Ardennes, December 16, 1944 – January 25, 1945; Central Europe, March 22 – April 25, 1945.

Support units attached to the 458th were: 60th Station Complement Sq., 469th Sub Depot, 1105th Quartermaster Company, 258th Medical Dispensary, 211th Finance Section, 2015th Aviation Fire Fighter Platoon, 1119th Military Police Company, 130th Army Postal Unit, 858th Chemical Company, 1686th Ordnance Supply and Material Company and 18th Weather Sq. Late in the tour, several of these units were combined into the 377th Headquarters and Base Service Squadron.

Group Commanding Officers

Commanding officers of the 458th and their tenure were: (L-R above) Lt Col. Robert F. Hardy of Flint, Michigan, July 28, 1943 – December 16, 1943; Col. James H. Isbell of Union City, Tennessee, December 16, 1943 – March 10, 1945; (Col. Isbell was the first officer in the 8th Air Force to command a single unit through 200 missions). Col. Allen F. Herzberg of Houston, Texas, March 10, 1945 – August 13, 1945; [After the Group’s return to the States, several men had a brief stint as CO]: Captain Patrick Hayes, (?), August 13, 1945, Maj. Bernard Carlos August 17, 1945, Maj. Valin R. Woodward August 22, 1945, and the last, Lt. Col. Wilmer C. Hardesty September 3, 1945.

Squadron Commanding Officers

752nd Squadron

Maj. John J. LaRoche

Maj. Walter H. Williamson

Maj. John A. Hensler

753rd Squadron

Maj. Frederick M. O’Neill

Maj. John A. Hensler

Not pictured: Capt. Elman J. Beth and Maj. Charles H. Breeding

754th Squadron

Capt. Estele P. Henson

Maj. Theodore J. Brevakis

Not pictured: Maj. David H. Phillip

755th Squadron

Lt. Col. Donald C. Jamison

Maj. Valin R. Woodward

Operations Officers were: Maj. Bruno W. Feiling, Lt. Col. Walter H. Williamson and Capt, Jack L. Bogusch. Medical officers were: Maj. William M. Routon, MD; Capt. Nathaniel T. Ballou, MD; and Capt. Seymour I. Shapiro, MD. Dental officer was: Capt. Porter R. Danford, DDS.

S/Sgt. Wells N. Gardner was a 46-year old gunner assigned to the 458th and completed more than 25 missions. He was also a WW I veteran and glider pilot. Sgt. DeSales Glover was also a gunner in the Group. He completed six combat mission, including the March 6, 1944 strike on Berlin. The he was found to be only 16-years old after enlisting in the AAF at age 14. He was returned to the U.S. and discharged (honorable). Thus the 458th has a rightful claim on having perhaps the oldest and youngest warriors of the air war in its ranks. [See: A Tale of Two Gunners]

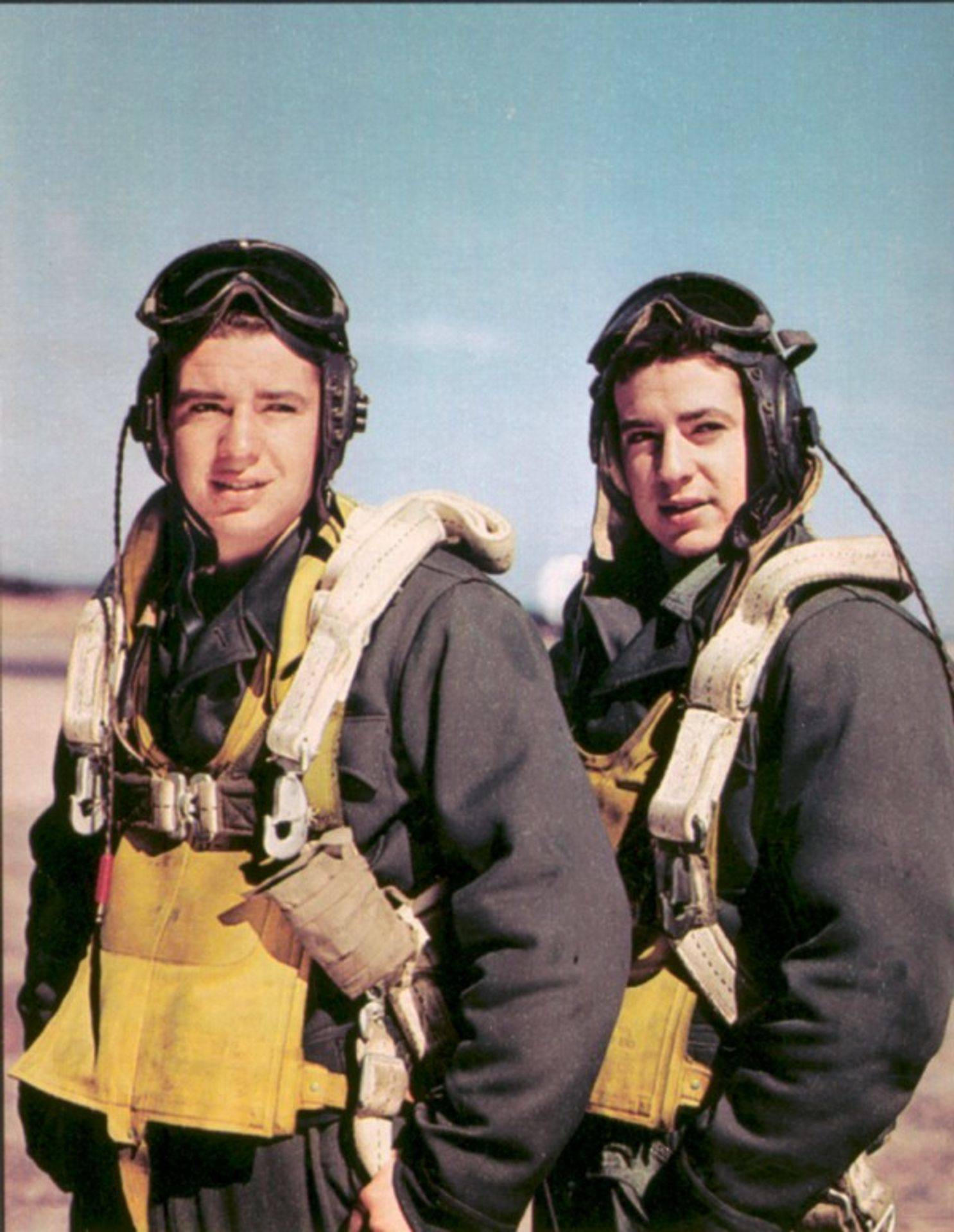

Twin brothers serving in the armed forces in WW II was not unusual. However, when they both were assigned to the same organization, especially as crew members on the same aircraft, it was very unusual! Don and John Echols [Capt Allen L. Blum crew] flew a number of missions together, but Don picked up a flak wound and their togetherness ended. Both left the military on a happy note.

One of the most renowned B-24 Liberators in the ETO flew with the 458th. Final Approach, serial 42-52457, was an H model in the 752nd Squadron. It was built by Ford at Willow Run, Michigan and modified at the Betchel-McCone-Parsons Center in Birmingham, Alabama. Its original crew gave it this nickname reminiscent of a landing back in the U.S. after the war was won.

The ship flew 113 missions before turning back from battle on an abort. She was lost on her 123rd mission April 9, 1945 at Lechfeld, Germany. One crewman was killed on this flight, and became the only known casualty among airmen flying the bomber. M/Sgt. Howard R. Hill and his assistant Sgt. E. H. Klase, had maintained Final Approach to perfection under the most harrowing weather and operational conditions imaginable.

Their work was the epitome of the 458th’s personnel attitude in general toward winning the war. This Group’s airmen never turned back from battle because of enemy action.

Target disparity for the 458th missions was:

(Targets of Opportunity have been omitted and numbers are approximate) airfields, 39; aircraft plants, 15; marshalling yards, 52; miscellaneous (factories, bridges, etc.) 54; No Ball (V-1 rocket sites), 11; oil facilities, 19; troops/gun emplacements, 8; waterways, 3.

This narrative is dedicated to those 309 members of the 458th Bombardment Group who paid the ultimate price in service to our country.

George A. Reynolds

Copyright, 1994 by Turner Publishing Company